For many, the world’s third-largest island of Borneo has a reputation for wild adventure, expansive rainforests, menacing headhunters, and a near-infinite inventory of flora and fauna. Perhaps in contrast, the village of Sukau on the Lower Kinabatangan River in Sabah is not well-known, as it has only been in the travel sights of adventurous tourists since the mid-1990s.

For countries like Malaysia, development and environmental protection are two words that you rarely see combined in one sentence. For this reason, ecotourism projects like that comprising the various plots of the 26,000-hectare Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary are perhaps best described as ‘islands in a sea of oil palm plantations’.

While the sanctuary is a forested island, it is also extensive enough to offer one of the best wildlife experiences in the whole of Borneo. There is an increasing appreciation that wilderness preserves, such as the Kinabatangan and others in the East Malaysian state of Sabah, have the sustainable potential to lure intrepid, nature-minded travellers for many decades to come if the forests are allowed to remain in their wild state.

Corridors of Power

Bormean Pigmy Elephant

One initiative that has come from the gazettal of the sanctuary is the establishment of wildlife corridors that connect the separate plots of the sanctuary and enable large animals to move around more freely without having to cross through oil palm plantations. On my recent visit, I was fortunate to see several Bornean pygmy elephants beside the bank of the river because they now have a large enough area of forest in which to roam. After countless trips into the backcountry over many, many years here, this was my first sighting of elephants in the wild anywhere in Malaysia.

Sabah’s Tourism, Culture, and Environment Minister, Datuk Masidi Manjun, recognised the urgency in establishing these wildlife corridors in forests previously isolated by plantations. He has also requested plantation owners to voluntarily establish natural areas for wildlife, and his government plans to work with the Malaysian Palm Oil Council to ensure a balanced approach between agriculture and environmental conservation.

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has worked in the area for a long time and has identified that in the Lower Kinabatangan, Borneo’s rarest wildlife reaches its greatest abundance. Animals with exotic names like flying lemur, slow loris, and tarsier are unknown to most but live here alongside other relatively rarities such as the Borneo pygmy elephant, proboscis monkey, and orang utan. Silver-leaf langurs and long-tailed macaques are seen virtually every day as troops of them run amok around most of the lodges in Sukau.

The Heart of Borneo

WWF has set out with their Heart of Borneo Project to protect the habitats of these species with an aim to create a network of protected areas to ensure the island’s natural resources are used sustainably. By 2020, WWF hopes to have 22 million hectares – or one-third of Borneo – included in a mosaic of protected areas that includes trans-boundary areas (those that extend over the national borders of Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia, the countries that share Borneo) and sustainably managed corridors.

The pygmy elephants I saw are endemic to Borneo, and with possibly only 2,000 remaining in the wild, trans-boundary parks are important for those that inhabit the forests along the border between Sabah and neighbouring Kalimantan, which is part of Indonesia.

Biodiversity is one of Borneo’s greatest treasures. WWF reported that in recent years, some 52 new animal and plant species have been identified by scientists in Borneo alone. This includes 30 fish, two tree frogs, 16 ginger plants, three tree species, and one large-leafed plant. One of the fish discovered is now recognised the world’s second-smallest vertebrate.

Eco-touring

Each afternoon, a small flotilla of boats transporting enthusiastic global travellers heads along a tributary of the Kinabatangan in search of wildlife. There seems to be sufficient room for the few boats that venture up here and there is still a sense of isolation in frontier lands along what is best described as a large creek rather than a river. Some of the lodges use electric motors to minimise the noise and eliminate the pollution from the fumes of petrol-burning motors.

The Menanggul River is the heart of the Kinabatangan, where there is a greater probability of seeing wildlife than anywhere else in the area. However, visitors soon appreciate that the Borneo rainforests offer a completely different wildlife experience to, say, the plains of Africa in that seeing the animals is certainly more difficult, but just as rewarding when they’re observed.

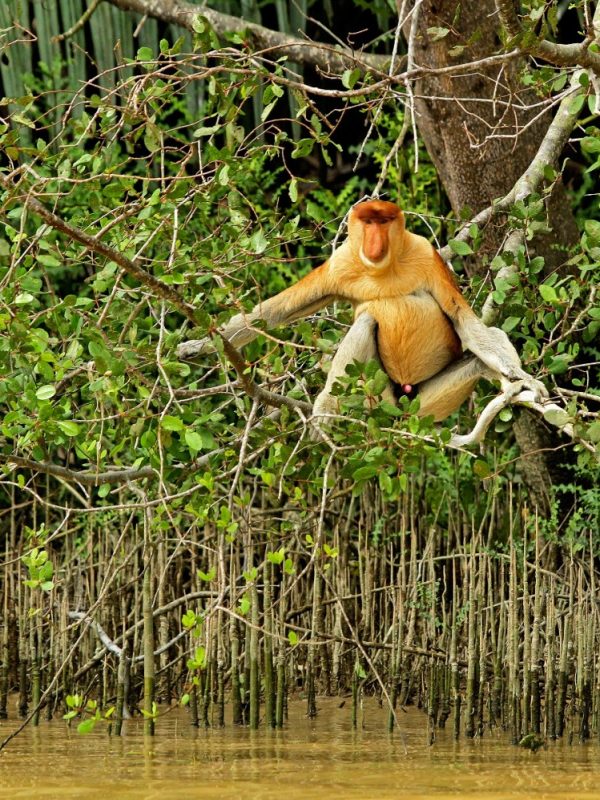

Within minutes, ever-playful young proboscis monkeys can normally be sighted amongst the dense riverine foliage. They are named for the huge pendulous red noses that the adult males display (they are also known as the long-nosed monkey). Proboscis monkeys are only found on Borneo, mostly within mangrove forests, and with numbers declining, they’re listed as endangered by international environmental organisations such as the IUCN.

They are surprisingly large animals with the males attaining a size of 70cm and weight of 20kg or more, but this doesn’t seem to affect their agility as they leap from branch to branch. They mostly live in families of about 20, and the alpha male is known to make threatening gestures to those who approach his harem.

As these monkeys are mostly orange and red with grey limbs, it’s not hard to spot them in the foliage, although the guides invariably manage to do this way before anyone else. On the ground, they mostly walk semi-upright and water is no obstacle, as they are also good swimmers. The distinctive barrel belly of the males led to the locals calling them monyet Belanda – or Dutch Monkey – which is the name neighbouring Indonesians gave the beast as, to them, it resembled the posture of some of the former Dutch colonialists (fair skin, big nose, and a ‘six-pack’ beer belly). If you embark on one of the boat journeys, binoculars certainly assist in getting a good look at these unusual primates and other wildlife.

Fauna Habitat

Orang utans are not so commonly seen and if they are, they’re almost always found alone, unless it is a mother with a young baby. I was fortunate to see two orang utans – one happily feeding on the plump sweet fruit of a fig tree and the other one building an impromptu nest to protect itself from an afternoon storm. The orang utan is a fairly sedate primate under ordinary circumstances, and is also considered the least social of the great apes.

Silver-leaf langurs are just as docile, but bands of the ever-active long-tailed macaques – the cheeky monkey familiar to most residents in West Malaysia – are commonly seen feeding high up in the rainforest canopy.

Reptiles are occasionally sighted on the ground, curled around tree limbs or sunning themselves on branches perched over the river. Huge monitor lizards are the ones mostly seen and if threatened they’re not averse to leaping into the water and swimming off to safety.

You have to be quick to see some of the birds, which are camouflaged, small, and agile. It’s hard not to notice the brilliant blue of blue-capped kingfishers, which are commonly sighted darting low across the river. In the undergrowth, rarely sighted crested firebacks may make an appearance just long enough to be hastily photographed and so, too, might the black-crowned night heron.

Back along the main river, some of the larger waders such as egrets and herons can be seen fishing in the river shallows. It’s not uncommon for a squadron of hornbills to sail overhead with a flurry of flapping wings. Enormous white-bellied sea eagles with long talons can also be seen swooping onto hapless fish.

At the end of a successful day in the heart of Borneo, places like the Sukau Rainforest Lodge are a welcome sight. Considering its isolation it is very comfortable with deluxe rooms, hearty local food, and plenty of cold beer and wines.

Nature tourism is well developed in Sabah, with Sandakan at the epicentre of the state’s northeast sector. Nature guides lead tours to the region’s other well-recognised natural areas such as Turtle Islands, Sepilok, Danum Valley, and Tabin Wildlife Reserve.

Getting There

AirAsia flies from either the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur or from the Sabah state capital of Kota Kinabalu to Sandakan with several flights per day. Malaysia Airlines also operates flights to Sandakan on most days, though all but one of them to/from KL involve a stop.

Accommodation

It is good to travel to the wilds of Borneo with the expectation that accommodation will be functional but a little rustic. After all, it’s in the middle of nowhere. That said, I was completely floored by the facilities at Sukau Rainforest Lodge (sukau.com) and its two categories of rooms, with the villas being the preferred accommodation. While there are many green practices in place here, the rooms are superbly fitted out with a contemporary Bornean ambiance. Packages are available that include all transfers (2.5 hours by boat from Sandakan), all meals, guided tours with local expert guides, and accommodation. This is a National Geographic Unique Lodge that offers barefoot luxury.

Tour Operators

Borneo Eco Tours (borneoecotours.com) offer specialised wildlife adventures in Sabah and also operates the lodge.

Contact

Sabah Tourism (sabahtourism.com) and WWF’s Heart of Borneo (panda.org).